This is the third in a series of posts about creating and utilizing a great program-centered budget. Click here to read Part I: Choosing to Create a Program-Centered Budget. Click here to read Part II: Choosing the Right Revenue and Expense Lines (and Naming Them Well).

Introduction

“Don’t tell me what you value; show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.”

A nonprofit’s annual budget has the capacity to be the most important communication tool the organization has – both internally and externally. A clear and purposeful budget can simultaneously provide trustees and staff the insights and understanding they need make mission-driven strategic decisions and inspire donors, program partners, and other constituents to engage with the organization.

A great budget tells a story about what we value – every bit as much as a great speech, brochure, website, or solicitation. When we develop a budget, it’s our obligation, and a great opportunity, to tell that story intentionally and directly – and (importantly) in a way that doesn’t make most readers feel like they’re reading a foreign language. I believe that the most compelling and effective way to do just that is through a “Program-Centered Budget.”

* * * * *

Part III: Allocating Shared Cost

This is the third installment in a four-part series of posts about creating and utilizing a great program-centered budget. In Part II, Pomsky puppies helped us talk about Choosing the Right Revenue and Expense Lines and Naming Them Well. And this installment is going to be particularly in-the-weeds. So I’m pleased to say that adorable Chow Chow puppies will be with us this time to help keep us all awake and engaged. (Hey, this is what works for me, no judgement.)

As we’ve discussed in both of the previous installments, a program-centered budget organizes itself around the primary programs (mission-focused activities) that the organization offers or undertakes. All shared expenses, from office supplies up to the chief executive’s salary, are allocated to either (1) one of the organization’s core programs/activities; (2) fundraising costs; or (3) G&A. So, let’s look how to accurately and efficiently allocate these cost in a way that fully adheres to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

Chow Chow Puppy Says: “Wait, what?! GAAP? Cost allocations? I have to tell you, I’m already feeling really overwhelmed by this piece.”

I appreciate you letting me know, Chow Chow Puppy. And I’ll tell you the truth – if you’re feeling that way, it’s totally ok for you to wait for (jump to) the fourth and final installment in the series, when we wrap everything up and talk a little about how we present our budget materials. This is going to be a wonkier-than-usual post as it explores the mechanics of cost allocation. And, though the ideas that follow absolutely don’t require any formal financial training, they are probably going to be of most interest to financial staff and Finance Committee members.

Two Problems with Over-Booking G&A

Some organizations simply book all (or an unnecessarily large portion of) shared costs as G&A. This causes two meaningful problems.

First, it leads to dramatically overstating G&A on audited financials and the IRS-990. Although the field has changed considerably in the last few years with the efforts of GuideStar and others to correct ill-informed perceptions about nonprofit overhead, donors still look at how much our organizations spend on G&A as a percentage of the total budget. So it’s important that we let donors compare apples to apples – by fully allocating shared costs, at the maximum level allowed by GAAP, so that the costs ultimately presented as G&A are accurate.

Even more damaging, in my opinion, it also dramatically understates the cost of our programs. It is imperative that staff and board leadership understand the full and true cost of all of the programs we undertake to achieve our mission. When we understate the cost of programs (by not including shared costs that are essential to executing the programs), we don’t have the accurate information we need to make thoughtful, strategic decisions about our organization’s priorities, activities, and future. Understating the true “philanthropic investment” required for each program (the full cost, less direct program revenue) also has a serious negative effect on our ability to effectively raise money, particularly major gifts.

Assumption of Departments

This piece will assume that our organization: 1) has departments and departmental budgets, and tracks expenses accordingly; 2) has three core programs, each of which has its own department; and 3) that our list of departments is as follows:

- Program Department #1

- Program Department #2

- Program Department #3

- Facilities

- I.T.

- Office Management

- Human Resources

- Finance

- Marketing

- Design

- Fundraising/Development

I understand that it’s unlikely that your real organization has this exact set-up. But these assumptions will allow us to explore the fundamental considerations when allocating shared costs – which should allow you to extrapolate and make the necessary adjustments and judgment calls as you apply the principles to your own structure and finances.

Order Matters for Booking Allocations

We are going to look at four categories of allocation – and order matters.

- Allocation of salaries comes first.

- Then we allocate costs related to facilities.

- Then we allocate shared administrative costs.

- Then we allocate shared non-administrative costs.

With the exceptions of salaries, all allocations are made through journal adjustments – and are generally booked either monthly or quarterly, depending on how often you prepare financial statements for staff (and board) leadership.

Chow Chow Puppy Says: “Excellent. As a nonprofit financial professional puppy, I’m excited to dive into the considerations for each of the four categories of allocation. Let’s do this!”

Allocation One: Salaries (including withholdings, taxes, benefits, etc.)

Employees fit into one of two categories: either they dedicate 100% of their time to one department or their time is divided between multiple departments.

If employees dedicate 100% of their time to one department, then they’re all set and no allocation is needed. (Note that we’re talking about departments, not programs, and that can make a difference as we’re thinking this through. For example, a full-time graphic designer would be designated as 100% to the Design department. As part of her/his work in the Design department, that designer works on projects for multiple other departments/programs. But we’ll address that use of her/his time when we allocate the design department in Allocation Four. This is a good example of why the order of allocation matters.)

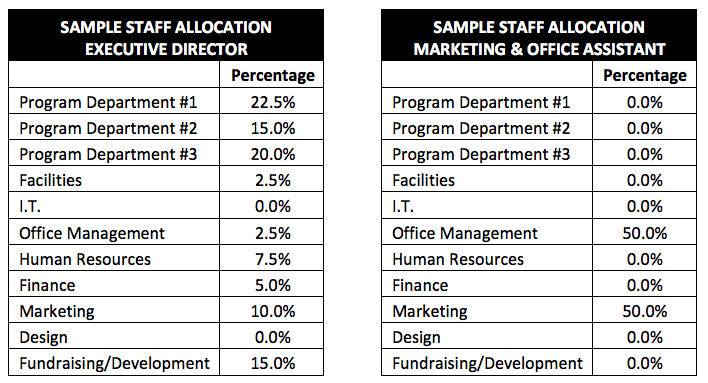

For employees who divide their time between multiple departments, the employee and the supervisor should work together to assess how their time is divided over the course of a full year. Often, this articulated division of a staff member’s time is explicit in an employee’s job description. (If it isn’t, this is something worth adding to the job description as soon as you’ve determined the division.) There is no need to create a timesheet or tracking system for this allocation, as that often takes far more time than the value added – though occasional check-ins to assess whether allocations still feel accurate are beneficial. Executive (and Artistic) Directors almost always dedicate their time to the work of multiple departments. And it’s critical that staff leaders’ time be allocated accurately. Beyond those leaders, organizations vary. Some have a fair number of employees who split their time between multiple departments; some have almost none. An example of an assessment could look like the following:

In most cases, the distribution of an employee’s salary and related costs to the appropriate departments is best accomplished through the payroll system itself. Almost any payroll system/vendor allows you to create departments into which you book staff costs. Many systems, in fact, require it. Once you have your percentages from the analysis above, simply use those percentages for each employee. Booking staff costs to the appropriate departments then happens automatically as part of our standard, recurring payroll booking/reconciliation.

Allocation Two: Facilities Related Costs

Square footage is the basis for allocation most commonly used for the Facilities department. This includes all costs related to facilities – staffing, rents, care and maintenance, etc. (It also includes depreciation, unless your organization tracks depreciation below the line.) This is accomplished by documenting the square footage each department uses – including all program, office, and other spaces. If a space is used by multiple departments, then we assess how much each department uses the space compared to the other(s), and split the square footage accordingly. This analysis will ultimately lead us to a table along the lines of the following:

From here, we allocate all costs in the Facilities department to the other departments, using the percentages we determined. In the sample above, you’ll note that, once we do this, we’ll have allocated out 98% of Facilities costs. The remaining 2% is essentially the Facilities Manager’s office.

Chow Chow Puppies Say: “We run the Finance, HR, and IT Departments, respectively. How are our costs allocated?”

Allocation Three: Shared Administrative Costs

Looking at our sample organization, the “administrative” departments are Finance, Human Resources, I.T., and Office Management. The most common basis for allocation for administrative functions is FTE (the number of full-time-equivalent employees in each department). Much of the work of these departments tends to be driven by employees themselves – such as Finance managing payroll, Human Resources managing performance reviews, Office Management making sure that all employees have the supplies they need, I.T. supporting individual equipment and support needs, etc. In most cases, the remaining functions also tend to correlate well to the number of FTEs. (If there were a specific reason that an administrative department did not follow this norm, financial and executive leadership at the organization would want to look at the reality of how the department’s resources are utilized and adjust accordingly.) Because we’ve already set up the salary/employee allocation, our payroll system/vendor will provide everything we need for us to do our FTE analysis, making it pretty easy for us to put something together along the lines of the following:

We then allocate all costs from each department (Finance, Human Resources, I.T., and Office Management) to the other departments, using the percentages we determined. As with Facilities, most (but not 100%) of the costs are ultimately allocated out, away from the administrative departments themselves. Which makes sense, as most of the work of these departments is to support the employees and activities of other departments, with only a small amount of time dedicated to supporting their own payroll, I.T, etc.

Grouping the Administrative Departments into G&A

Once Allocation Three has been completed for each of the four administrative departments (Finance, Human Resources, I.T., and Office Management), the four departments should be grouped together as G&A – as audited financials and the IRS-990 will ask us to present all expenses as either Program Services, Fundraising, or G&A. (Many organizations will already have this grouping in how they’ve set up their financial systems and reporting, with those four departments listed as sub-categories of G&A.)

Allocation Four: Shared Non-Administrative Costs

Looking at our sample organization, the “non-administrative” departments are Marketing & Design. 100% of the costs in these two departments will ultimately be allocated out to a specific program department or fundraising (or, on rare occasions, to G&A*). For these two departments, subjective assessment is the most common and effective basis for allocation. Department leaders should examine both our hard-cost spending and the activities of our employees to develop an assessment of how much of total departmental resources are utilized for each program department – and for fundraising, if there is any direct service to the Development department. The assessment will ultimately lead us to tables along the lines of the following:

*It is rare for shared non-administrative costs to be allocated out G&A, but not completely unheard of. For example, there could be instances where a Design department did work for an administrative department – perhaps creating a new design for checks that the Finance Department uses. Often, even when this happen, so little time is spent that it’s not worth incorporating an allocation. However, if enough of such work happens that external auditors might find it “material,” then a percentage for G&A should be included in a table like the one above. If that happens, finance staff would need to create a system for making that allocation before Allocation Three happens, and for addressing any circular formulas that arise from the process.

Similar to the staff-focus analysis in Allocation One, it is beneficial to conduct check-ins to assess whether the allocations still feel accurate, with a particularly in-depth review at the end of the fiscal year – and to adjust the allocations accordingly.

Conclusion

Those are all four of the steps needed to appropriately allocated shared costs. All of our costs now are booked to one of our core programs, to fundraising, or to G&A – giving us accurate clear and accurate information about how much we spend on each program, fundraising, and G&A.

Chow Chow Puppy Says: “Nice. Thanks. I’m going to start right n… Squirrel! Squirrel! Squirrel!”

Ok. Bye, Chow Chow Puppy.