This is the fourth and final post in a series about creating and utilizing a great program-centered budget. Click here to read Part I: Choosing to Create a Program-Centered Budget. Click here to read Part II: Choosing the Right Revenue and Expense Lines (and Naming Them Well). Click here to read Part III: Allocating Shared Cost.

Introduction

“Don’t tell me what you value; show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.”

A nonprofit’s annual budget has the capacity to be the most important communication tool the organization has – both internally and externally. A clear and purposeful budget can simultaneously provide trustees and staff the insights and understanding they need make mission-driven strategic decisions and inspire donors, program partners, and other constituents to engage with the organization.

A great budget tells a story about what we value – every bit as much as a great speech, brochure, website, or solicitation. When we develop a budget, it’s our obligation, and a great opportunity, to tell that story intentionally and directly – and (importantly) in a way that doesn’t make most readers feel like they’re reading a foreign language. I believe that the most compelling and effective way to do just that is through a “Program-Centered Budget.”

* * * * *

Part IV: Presenting Our Program-Centered Budget

The Full Budget

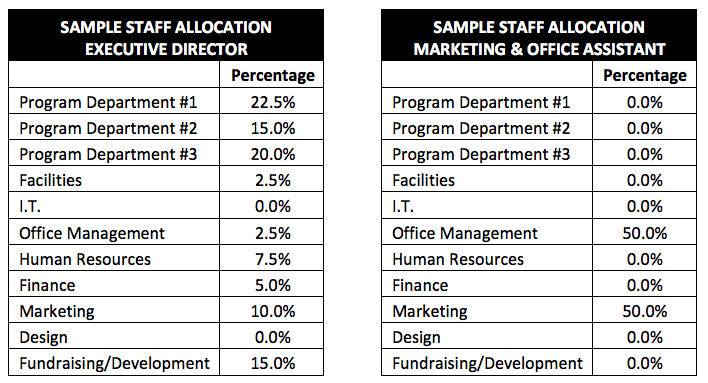

Taking as a given that we’ve categorized and named our revenue and expense lines to reflect what we value and what we want external and internal constituents to understand (as explored in Part II of this series), here is a sample of what a what a summary program-centered budget looks like.

Even people who don’t spend a lot of time with financial statements should be able to look at this budget and easily understand 1) where funding comes from, and 2) how funds are invested to accomplish the organization’s mission. In addition to offering a straight-forward budget in “table” format, our organization of the budget also lends itself well to graphics to tell our story. For example, an easy way to convey where our funding comes from would be…

The visual makes it very clear: a little more than half our funding comes from public support (contributions), a little less than half comes from performance revenue (subscriptions, tickets, and on-site retail), and a small sliver comes from other sources. Depending on the purpose and audience of our graphic, we could create additional or different graphics to further break down sources of public support or performance revenue. But this simple graphic, coupled with the full budget, tells a clear story about our revenue.

What Graphics of the Other Budget Types Expenses Would Look Like (The Ones We Do Not Want)

On the expense side, looking at graphic representations underlines why a program-centered budget is the best approach. So let’s take a quick look at what our pie charts would look like with the other two budget types.

The graphic above reinforces what we discussed in Part I about why a functional budget is of almost no value to board members and other internal constituents, and even less to donors and other external stakeholders.

As we’ve discussed, a departmental budget is a frequently-used approach to budgeting. But when you look at it as a graphic, it shows itself to be even worse than a functional budget, in many ways. The functional budget chart is mostly just useless and confusing to see as a chart. But for the departmental budget, because shared expenses have not been allocated to the programs that are sharing them, the chart is actually very misleading. Looking at this graphic, you might reasonably come to the conclusion that the organization spends about half of its budget on its three programs combined (in green, on the left of the chart) – and that a whopping 48% of the budget is spent on activities other than the programs the organization exists to offer. This, of course, is not the case – and presenting the numbers that way to internal and external stakeholders does everyone a great disservice.

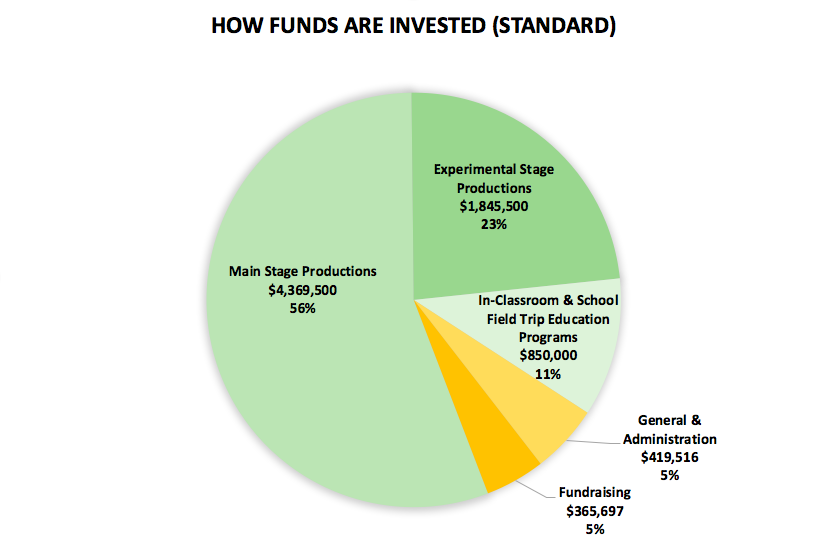

Expenses Chart – Standard Representation of Program-Centered Budget Expenses

In a program-centered budget, shared expenses are accurately allocated to the programs that share them, so our expense lines are the programs we offer, fundraising expenses, and unallocated general and administrative expenses. This offers readers a clear and accurate picture of how funds are invested. Going back to Theatre ABC and our budget above, a standard program-centered pie-chart would look like this:

This chart is tells our story more accurately and more clearly than the charts for functional and departmental budgets.

Expenses – An IMPROVED Representation of Program-Centered Budget Expenses

In terms of presentation, we can could stop with the program-centered budget table, revenue chart, and expense chart and have a meaningful and effective set of communications tools. That said, I’d like to share a way that we can make our expense graphic even more effective. In a recent an article in The Nonprofit Quarterly magazine, Curtis Clotz, of the Nonprofit Assistance Fund, suggests that we categorize fundraising and G&A together as “Core Mission Support.” (You may recall that, in Part II of this series, I grouped fundraising and G&A as “Support Services,” as I’ve always thought it was important to make clear that both existed to make our core programs possible – not as costs in a vacuum that take away from our programs. But I like Mr. Clotz’s “Core Mission Support” even better, and have changed the category name in the budget and graphics above.

In the article, Clotz articulately calls out the central drawback of the standard program-centered expense pie-chart:

“When nonprofits are viewed this way, no matter how hard we try to think differently, we imagine important infrastructure of our organization as taking a slice out of the pie—as diminishing the “real” work of our mission. Strategic financial functions, good governance, and the development of key funding partnerships are vital to strong organizations. We need a new way to communicate this truth.” He goes on to suggest that this core mission support could be presented in the center of the pie, “rather than thinking of our investment in key infrastructure as diminishing our programs.”

This idea of literally placing Core Mission Support at the core of our budgets is both elegant and exciting. Incorporating the idea into a graphic that can be used to effectively communicate specific budget figures, the improved pie chart could look something like this:

The graphic representation of our budget now conveys two different important messages:

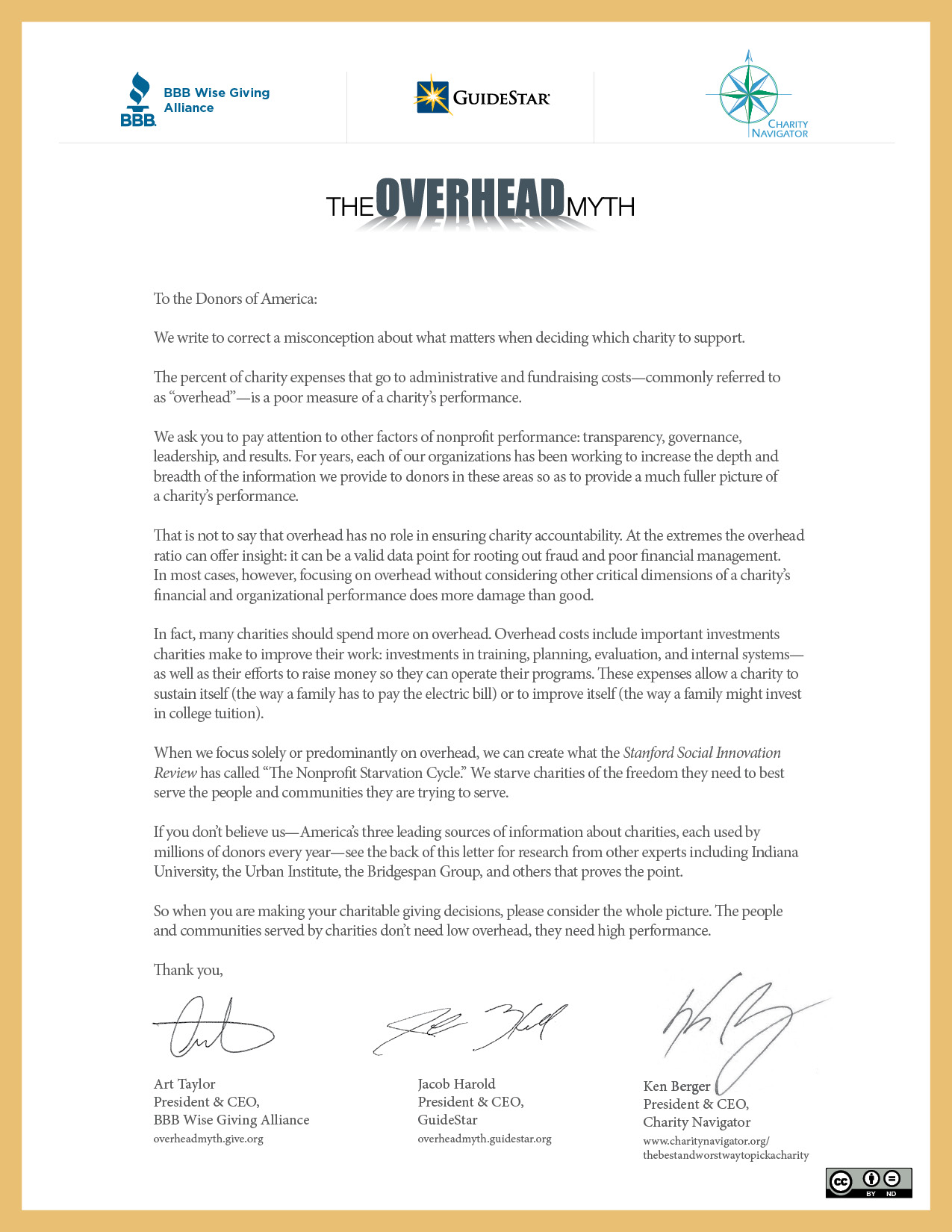

- The ratio of direct program services to core mission support (90%/10%). Although the field has changed considerably in the last few years with the efforts of GuideStar and others to correct ill-informed perceptions about nonprofit overhead, there are still donors want to know how much of our budget is comprised of Fundraising and G&A – and we want to make it easy for them to see and understand that ratio.

- How much of our full budget we dedicate to each of the mission-driven programs we offer (62%/26%/12%). Note that these percentages include a pro-rated portion of the core mission support expenses. Since we’ve already called out the ratio of direct and support costs, we are able to separately look at the full cost of our programs, showing how much of the pie we dedicate to each totaling 100%.

This approach requires a little bit of design work, as it’s not a stock Excel chart. And the standard pie chart for program-centered expenses certainly gets the job done well (and far better than with any other type of budget). But this strikes me as an exciting way to take our expense infographics to the next level.

In Summary

As this is the last installment, let’s wrap it up with some key take-aways from the entire four-part series.

- Great budgets simultaneously give trustees and staff the insights and understanding they need make mission-driven strategic decisions and inspire donors, program partners, and other constituents to understand and engage with our organizations.

- Functional and departmental budgets don’t allow us to tell our story well.

- Program-centered budgets allow us to clearly convey what do we do/accomplish, how much it costs, and where the funding comes from.

- We get to name our revenue and expense lines however we like, and we can pick the wording that best expresses what we value and accomplish.

- It is imperative that we allocated shared costs. Not doing so dramatically overstates G&A, which makes many nonprofits look like they’re spending more on G&A than they are and than the norm– and likewise understates the cost of our program services, which prevents us from having the accurate information we need to make thoughtful, strategic decisions about our organization’s priorities, activities, and future.

- Once we have a well-organized program-centered budget with intentional and evocative naming and allocated shared costs, we are able to present budget tables and infographics that tell our story clearly and compellingly. (The ones in this fourth installment and, of course, many more – depending on what elements of our story we want to emphasize.

Thanks for coming on this budgety journey with me. I get pretty geekishly excited about great budgets – so if you create or already have a program-centered budget for your organization that you like, please share it with me at the email address below. I’d love to see it.